|

|||||

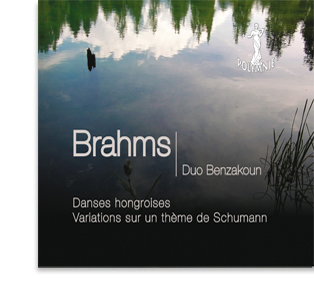

Brahms

• Danses

hongroises • Variations sur

un thème de Schumann, op. 23

Duo

Benzakoun

Laurence Karsenti, Daniel Benzakoun •

Piano à quatre mains

POL 101 100

Commander

sur Clic Musique !

Brahms

Danses hongroises

Variations sur un thème de Schumann, op. 23

C’est à l’âge de

quinze ans que Brahms entre en contact avec la musique hongroise.

En 1848, la révolution en Hongrie provoque à Hambourg un afflux

de réfugiés qui cherchent à embarquer pour le Nouveau monde.

Parmi eux, un violoniste hongrois de grand talent qui a étudié

à Vienne, Eduard Remenyi et qui, grâce à sa virtuosité

extraordinaire, devient célèbre à Hambourg, où l’on va lui

proposer Brahms comme accompagnateur.

Les deux jeunes gens fraternisent et se produisent dans la ville

et ses environs dans un programme de danses populaires hongroises

grâce auquel ils remportent un grand succès. Remenyi part pour

l’Amérique mais en revient rapidement pour se fixer à Hambourg

en 1853. En avril de cette année, les deux compères partent en

tournée (à pied!) dans le nord de l'Allemagne ; au programme de

leurs concerts, une sonate de Beethoven, un concerto de

Vieuxtemps, des danses et mélodies hongroises dont Brahms

improvisait certainement les accompagnements.

En mai, ils vont à Hanovre sonner à la porte d’un autre

violoniste hongrois, condisciple de Remenyi à Vienne, Joseph

Joachim. Celui- ci, déjà très célèbre à l’époque, allait

devenir l’ami très cher de Brahms. C’est au cours d’un voyage que

feront Joachim et Brahms à Budapest en novembre 1867 que ce

dernier aura accès à des publications de musique populaire

hongroise.

Dès cette période, Brahms arrange ces mélodies pour piano solo

et les joue en public.

Clara Schumann en joue elle-même dans ses concerts, et Brahms les

transcrit pour piano à quatre mains. Le 30 octobre 1868, Clara

Schumann et Johannes Brahms donnent l’intégrale des danses

hongroises au cours d’un concert privé.

En réalité, la véritable musique folklorique hongroise est

celle qui a été révélée par les travaux musicologiques de

Bartok et Kodaly au début du XXème siècle; la musique dont il

est ici question est la musique tzigane, importée d’Orient

(l’anglais gypsy vient du mot («égyptien»), interprétée par des

orchestres de musiciens itinérants. Elle utilise des rythmes, des

intervalles, des modes et des formules caractéristiques.

Constitués de deux violons, d’une contrebasse et d’un cymbalum

auxquels s’adjoint parfois une clarinette, ces orchestres, souvent

employés par l’armée, jouent le Verbunkos (de l’allemand

Werbung), une danse destinée à attirer de nouvelles recrues, qui

évoluera au XIXème siècle vers la csardas.

Cette danse se caractérise par une introduction lente, ou lassu,

suivie d’une section rapide ou friska. S’y côtoient des passages

très expressifs et des accélérations, des changements brusques

de tempo, des trilles, des trémolos, des syncopes, que les

orchestres tziganes exécutent avec la plus grande liberté, et

où entre une grande part d’improvisation.

Cette musique a marqué bon nombre de compositeurs

dont Haydn, Beethoven, Schubert et Lizst ; chez Brahms, qui en a

été nourri depuis l’adolescence, son influence est perceptible

dans les Zigeunerlieder, les finales du Quatuor en Sol Mineur et

du Concerto pour Violon, les Variations sur une Mélodie hongroise

et les Danses hongroises.

Les Danses hongroises furent publiées sans numéro d’opus, c’est

dire que Brahms ne les considérait pas comme des créations

originales, mais comme des arrangements pour le piano à quatre

mains de mélodies existantes. Trois de ces danses sont

entièrement dues à Brahms : les danses 11,14 et 16.

Les 21 danses sont réparties en quatre cahiers, de respectivement

5, 5, 6 et 5 danses. Chaque cahier forme un tout : l’enchaînement

des tonalités, l’alternance de danses relativement lentes ou

rapides, la conclusion de chacun d’entre eux par une danse

particulièrement brillante, donnent à penser qu’ils sont

destinés à être joués dans leur intégralité. On peut

également remarquer l’empreinte d’une danse sur la suivante,

comme par exemple, la danse 13 qui reprend le rythme de la 12 mais

dans un tempo et un caractère complètement différents, ou la

danse 15 dont l’introduction est la conclusion transposée de la

14.

On ne saurait mieux décrire l’art avec lequel Brahms a animé, enrichi, magnifié ces mélodies tziganes que dans la lettre quelui adresse une de ses amies, Elisabeth Von Herzogenberg (23 Juillet 1880) : « ... Ce mélange de tourbillons et de trilles, ces cliquetis, ces sifflements, ce fracas de gargouillis, tout est reproduit de telle manière que le piano cesse d’être un piano, et que l’on est transporté au milieu des violoneux. Quelle merveilleuse sélection vous en avez faite cette fois, et combien plus vous rendez que vous n’avez pris ! Par exemple, il est impossible d’imaginer – à moins que je ne me trompe - qu’une mélodie comme celle de la danse en mi mineur, numéro 20, ait pu être traduite d’une si parfaite manière, particulièrement la seconde partie, si ce n’est par vous. Votre touche est le coup de baguette magique qui donne vie et liberté à tant de ces mélodies. Ce qui m’impressionne le plus dans votre performance, cependant, est que vous êtes capable de transformer en un tout artistique ces éléments de beauté plus ou moins cachés, et de les élever au plus haut niveau, sans qu’ils aient perdu de leur sauvagerie primitive et de leur vigueur. Ce qui était à l’origine du bruit est façonné en un beau fortissimo, sans jamais dégénérer non plus en un fortissimo poli. Les différentes combinaisons rythmiques enfin, qui semblent vous venir avec tant d’à-propos, vont parfaitement ici, et sont étonnamment efficaces comme, par exemple, les délicieuses basses dans la tumultueuse danse numéro 15. Celle-ci serait ma préférée, s’il n’y avait pas les numéros 20, 18, 19, et la courte, douce numéro 14 ! Si je devais dire tout ce qui est possible à propos de ces danses, je devrais citer passage après passage, jusqu’à ce que j’aie tout copié... »

Un autre compositeur a mesuré toute l’importance

qu’il faut accorder à la musique folklorique ; c’est Robert

Schumann, qui écrit dans ses "Règles de conduite du Musicien":

« Ecoute bien tous les chants populaires ; c’est une mine

inépuisable des plus belles mélodies ... »

C’est aussi ce compositeur qui, souffrant d’hallucinations

auditives, au soir du 17 Février 1854, entend le fantôme de

Schubert ou de Mendelssohn lui dicter un thème. Celui-ci avait

été utilisé dans plusieurs de ses œuvres auparavant : le

mouvement lent du concerto pour violon, le deuxième quatuor à

cordes, son album de lieder pour la jeunesse. Schumann écrit

alors cinq variations sur ce thème, connues comme

Geistervariationen, ou Variations des Esprits, avant d’aller se

jeter dans le Rhin.

Brahms va également utiliser ce thème pour écrire

une série de variations ; l’œuvre est un hommage au maître et

ami et est dédiée à Julie Schumann, la troisième fille du

compositeur. Brahms décrit le thème comme une « pensive,

doucement murmurée parole d’adieu ».

La première variation reprend le thème, délicatement enveloppé

d’arabesques de doubles croches. La seconde, plus rythmique, est

plus agitée ; la troisième, typiquement brahmsienne par la

superposition de rythmes binaires et ternaires, est plus

mouvementée encore tandis que la quatrième, avec son canon qui

émerge de sourds grondements à la basse, est extrêmement

sombre. De la lumière revient avec la variation cinq, d’une

douceur extraordinaire. La tonalité initiale réapparaît avec la

sixième variation, au caractère beaucoup plus affirmé que la

septième, qui est un capricieux dialogue entre l’aigu et la

basse. La huitième, au caractère plus haletant, laisse la place

à l’avant-dernière, aux sauvages débordements de triples

croches. La paix revient avec la dixième variation, sur un rythme

de marche funèbre, sur lequel va réapparaître le thème initial

en un dernier adieu. Une des plus belles pages du compositeur.

Laurence Karsenti

![]()

Le Duo Benzakoun

Rares sont les duettistes qui se vouent à leur art avec autant de

talent, de passion et de bonheur.

Que le Duo Benzakoun collectionne de 1988 à 1991 les prix

internationaux en Italie ou aux Etats Unis, qu’il se produise en

concert en duo (USA, récemment le Kennedy Center de Washington ou

le Centre Culturel de Chicago, en Autriche, Angleterre, Italie,

Israël, Chypre, Canada, Mexique, Madagascar, Norvège..., en

France - salle Cortot, Musique en Sorbonne, la Grange de Nohant,

des tournées Région Centre...), en concerto avec l’orchestre de

Tours-Région-Centre dir. J.Y. Ossonce dans le concerto de

Poulenc, en spectacle musical espagnol Evocacion avec la soprano

Corinne Sertillanges, en concert théâtral intitulé avec humour

: Quand Mozart est là... ou encore dans le Carnaval des Animaux

avec la compagnie Clin d’oeil, chacune de ses apparitions est un

moment inoubliable de musique. Le duo tourne également dans

différentes Scènes Nationales depuis 2009 avec un programme

entièrement consacré à Schubert. Le public et la critique ne

s’y trompent pas : « ... les deux pianistes s’affichent en

duettistes parfaits, leur qualité principale étant la réussite

la plus lisible possible des équilibres sonores de l’écriture et

des émotions qui en émergent » (Ouest-France - 10/01).

Déjà vingt ans de carrière internationale et

l’enthousiasme de ces deux «Artist Diploma» de l’Académie Rubin

de Jerusalem, formés auprès du Duo Eden-Tamir (1986), ne tarit

pas, bien au contraire !

La production discographique du Duo Benzakoun, largement diffusée

sur France Musique, France Inter, en témoigne. Débutée en 1994

avec l’oeuvre pour 2 pianos de Brahms, elle se poursuit en 1999 de

Ballets Russes chez Mandala dist. Harmonia Mundi, en 2001 d’un

C.D. Ravel - Oeuvres pour 2 pianos chez INTEGRAL classic (8 de la

revue Répertoire), en 2003 d’un C.D. Poulenc à deux Pianos

salué par une presse unanime: Recommandé par les revues Classica

et Répertoire et Coup de coeur de Piano- Magazine. Un CD

consacré à Rachmaninov est paru en 2005, suivi en avril 2008

d’un disque Debussy, salué par la critique.

www.duobenzakoun.com

![]()

Brahms’s first contact with

Hungarian music occurred when he was fifteen. In 1848, the

Hungarian revolution led to an influx of refugees that came to

Hamburg, seeking embarkation for the new world. Among them was

Eduard Remenyi, a highly talented violinist who had studied in

Vienna, and whose extraordinary virtuosity allowed him to gain

fame in Hamburg; this is where Brahms would soon be suggested to

him as his accompanist. The two young men formed a friendship

and performed in the city and its surroundings, playing a

program of Hungarian popular dances that gave them great

success. Remenyi departed for America, but soon came back to

settle in Hamburg in 1853. In April of the same year, the two

fellows set out on a tour in Northern Germany (by foot!); their

concert program featured, among others, a sonata by Beethoven, a

concerto by Vieuxtemps as well as Hungarian dances and melodies,

the accompaniments of which were certainly improvised by Brahms.

In May 1853, they went to Hanover to knock on the door of

another Hungarian violinist, Joseph Joachim, who had been

Remenyi’s fellow student in Vienna. Joachim, who was already

famous at that time, was to become Brahms’s very dear friend. It

is during a journey undertaken in November 1867 by Joachim and

Brahms that the latter got access to publications of Hungarian

popular music.

During this period, Brahms started to arrange those melodies for

piano solo, and performed them in public; Clara Schumann herself

would play them in her concerts. Then, Brahms transcribed his

arrangements for piano four-hands. On October 30th 1868, Clara

Schumann and Johannes Brahms played the complete series

of Hungarian dances during a private concert. The truth is that

the real Hungarian folk music is the one which was revealed by the

musicological works of Bartok and Kodaly, in the early 20th

century. What is developed here is gypsy music: the one imported

from the East («Gypsy» deriving from the word «Egyptian»), using

specific rhythms, intervals, modes and phrases, performed by

traveling musicians orchestras. Composed of two violins, one bass

and one cymbal, and sometimes one additional clarinet, these

orchestras -which were often hired by the army, would play the

Verbunkos (from the German Werbung), a dance meant to attract new

recruits and which evolved during the 19th century towards the

Csardas.

This Verbunkos dance is characterized by a slow introduction, or

lassu, followed by a rapid section, or friska. It unfolds very

expressive moments along with faster rhythms, sudden tempo

changes, trills, tremolos and suspensions; all these were

performed by gypsy orchestras with the greatest freedom, and with

a great part of improvisation.

This music has struck many composers, including Haydn, Beethoven,

Schubert and Lizst; in the works of Brahms, who has been inspired

by it since his adolescence, this gypsy influence can be perceived

in the Zigeunerlider, in the finales of the Quatuor in G Minor, in

the Violin Concerto, in the Variations on a Hungarian Song and in

the Hungarian Dances.

The Hungarian Dances were published without any opus

number, which indicates that Brahms did not consider them as

original creations, but as the arrangements of already existing

melodies for piano four-hands. Three of these dances were entirely

composed by Brahms: the dances No.11, No.14 and No.16.

The 21 dances are divided into four books, featuring respectively

5, 5, 6 and 5 dances. Each book is composed as a whole: the

enchainment of tonalities, the alternation of relatively slow or

rapid dances, the conclusion of each book with a particularly

brilliant dance, all these features suggest that each book is

meant to be played in its entirety. One can also notice the

impression left by one dance on the next: for instance when the

Dance No.13 uses the same rhythm as that of the previous dance,

but with completely different tempo and character, or in the Dance

No.15 where the introduction is actually the transposed conclusion

of the Dance No. 14.

There is no better description of how Brahms’s art animated,

enriched and magnified those gypsy melodies than in the letter

sent by one of his friend, Elisabeth Von Herzogenberg (January

23rd 1880):

«[...] This medley of twirls and grace-notes, this jingling,

whistling, gurgling clatter, is all reproduced in such a way that

the piano ceases to be a piano, and one is carried right away into

the midst of the fiddlers. What a splendid selection you borrowed

from them this time, and how much more you give back than you

take! For instance, it is impossible to imagine -though I may be

mistaken- that a melody like that E minor. Number 20, could ever

have taken on such a perfect form, particularly in the second

part, if not by you. Your touch was the magic which gave life and

freedom to so many of these melodies. What impresses me most of

all in your performance, though, is that you are able, out of

these more or less hidden elements of beauty, to make an artistic

whole, and raise it to the highest level, without diminishing its

primitive wildness and vigour. What was originally just noise is

refined into a beautiful fortissimo without ever degenerating into

a civilized fortissimo either. The various rhythmical combinations

at the end, which seem to have come to you so apropos, would only

fit just there, and are amazingly effective -as, for example, the

delightful basses in tumultuous Number 15. That one would be my

favourite, anyway, if there were not Numbers 20, 19, 18 -oh, and

the short, sweet Number 14! If I were to try and tell you all we

have to say about these dances, I should have to quote passage

after passage, until I had copied out nearly the whole of the

‘Hungarians’[...]».

Another composer did measure the importance of folk

music, namely Robert Schumann, who wrote in his “Rules for Young

Musicians”: Listen attentively to all folk songs ; these are mines

of the most beautiful melodies...

In the evening of February 17th 1854, that same composer, who was

suffering from auditory hallucinations, heard the ghost of

Schubert or Mendelssohn utter and dictate a musical theme to him.

This theme had been used in many of his previous works: in the

slow movement of the Concerto for Violin, in the Second String

Quartet and in his Lieder Album for the Young. Right after this

ghostly vision, Schumann translated that same theme into five

variations, known as the Geistervariationen or Ghost Variations,

before throwing himself into the Rhine river.

Brahms also used this theme to write a series of variations; this

work was a tribute to his master and friend, and was dedicated to

Julie Schumann, the composer’s third daughter. Brahms described

the theme as a "thoughtful, softly whispered farewell". The first

variation takes up the main theme and delicately wraps it up in

sixteenth notes arabesques. The second variation is more

rhythmical and agitated; the third one, which is typically

Brahmsian in its superimposition of binary and ternary rhythms, is

even more hectic, while the fourth variation conveys an extremely

dark atmosphere, playing a canon that emerges from the muffled

rumbles of the bass. Light is brought back by the fifth variation

and its extraordinary softness. The initial tonality reappears in

the sixth variation, the assertive character of which contrasts

with the seventh variation and its whimsical dialogue between

sharp and bass voices. The eighth variation displays a more

panting character, before giving way to the wild overflow of

thirty-second notes that spread out in the second-last variation.

Peace comes back with the tenth variation, at the pace of a

funeral march, where the initial theme reappears as an ultimate

farewell. It is one of the composer’s most beautiful pages.

Laurence Karsenti

![]()

It is very rare to encounter artists who fulfil

themselves as duettists with so much talent, passion and

happiness.

Ever since the beginning of their career, the Duo Benzakoun has

been giving outstanding performances, collecting many

international competition awards between 1988 and 1991, playing in

concerts halls, and producing creative, cross- disciplinary shows.

Their performances in France include the Salle Cortot, Musique en

Sorbonne, la Grange de Nohant, as well as several tours in the

Region Centre. The Duo Benzakoun’s most recent international tours

include England, Norway, Italy, Austria, Israel, Mexico,

Madagascar, Canada, Cyprus... They have also performed at the

Kennedy Center in Washington D.C., and at the Chicago Cultural

Center.Their repertoire embraces works by celebrated composers -

Mozart, Schubert, Ravel, Stravinsky, Rachmaninoff, Poulenc’s

Concerto for Two Pianos-, but also original creations: a Spanish

music piece entitled Evocación, performed with soprano singer

Corinne Sertillanges, and a praised theatrical performance based

on Saint-Saën’s Carnival of the Animals, performed with the

company Clin d’Œil. Audiences and critics are unanimous: “The two

pianists appear as perfect duettists; their main quality lies in

the sound balance emanating from the writing, and in their

capacity to successfully reveal the emotions which transcend the

musical work.” (Ouest France)

Both pianists hold a Bachelors of Arts degree from the Jerusalem

Rubin Academy (1986), where they received training under the

Eden-Tamir Duet.

Enriched by an international experience of over two

decades, the Duo Benzakoun now ranks among the best interpreters

as regards the repertoires for two pianos, piano four-hands and

two pianos with orchestra.

Their discography also testifies to their talent and active

commitment. The Duo Benzakoun recorded their first disc, Brahms’s

Work for two pianos, in 1994, and they have continued to record

several compact discs ever since. In 1999, they thus recorded a

program of Russian Music for Piano Duet (produced by

Mandala/distributed by Harmonia Mundi). In 2001, INTEGRAL Classic

released a recording dedicated to Ravel’s Works for Two Pianos,

which was positively welcomed by music critics and highly ranked

by Répertoire Magazine. Two years later, INTEGRAL Classic

produced their fourth recording, Poulenc for two pianos. The

latter was widely acclaimed by the press, commended with a

“Recommandé” from Répertoire, and presented as Piano Magazine’s

“Coup de Coeur”. Slava, a recording dedicated to Rachmaninov’s

pieces for duet and two pianos, was released in 2005, followed in

2008 by a disc dedicated to Debussy, featuring the world’s first

recording of “Sirènes”.

www.duobenzakoun.com

![]()

Accueil | Catalogue

| Interprètes | Instruments

| Compositeurs | CDpac

| Stages | Contact

| Liens

• www.polymnie.net

Site officiel du Label Polymnie • © CDpac • Tous droits

réservés •